Death and the Sublime

“…somehow they understood that the circle between death-worship and death-wish had been completed for another year and the crowd went completely loopy, convulsing itself in greater and greater paroxysms.”

– Stephen King as Richard Bachman, The Long Walk, 1979

“…that echo beyond time, anguish or caress…

Are we near to our conscience, or far from it?”

– Jean Luc-Godard, Alphaville, 1965

—

Recently I overheard a vociferous diner in a restaurant on the Upper West Side describe his dessert as “delicious, simply sublime.” That must have been some chocolate cake to make him suddenly aware of the fragility of his own life within nature’s overwhelming power. Or did he just mean it was good cake?

Today the word “sublime” has been decontextualized to the point where it has lost its original meaning. The earliest 18th century definitions involve the experience of being struck by the boundlessness of nature, mingled with an “agreeable kind of horror,” as in the Italian Alps.1 Edmund Burke was the first to establish a visceral-aesthetic parallel between the beautiful and the sublime. To Burke, the sublime is more powerful and intense than the classical Platonistic pure pleasure notion of beauty. Instead, the sublime produces a “negative pleasure” or “delight”.2 In A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Part I, Section VII, Burke elaborates, “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.”3

Burke alludes to the prospect of death. An essential caveat he later adds: “Nor is it, either in real or fictitious distresses, our immunity from them which produces our delight…it is absolutely necessary that my life should be out of any imminent hazard, before I can take a delight in the sufferings of others, real or imaginary.”4 Ultimately, he would argue that we all have a death wish, as long as actual death and destruction stays imaginary.

What Burke does not explicitly address is human nature. The craving for the sublime is basic, embedded within us. We all have an innate desire to be put out of place, to get close to destruction without actually being destroyed. To be seduced by a power greater than us. This compulsion along with our capacity to truly experience the sublime develops as our impressions of the world are formed. As such, adults typically have a more natural appreciation of the sublime than do children, who are highly perceptive yet generally naive. The desire to be put out of place extends to people of all race, gender, and personality. It is not limited to the adrenaline junkie who seeks thrills for the sake of the thrill, nor is it masochism because it does not induce conventional pain. The sublime is equal opportunity, and it is always more than.

Though the sublime is a highly intimate individual experience, it is the ultimate unifier. It strips away unnecessary delineations, blowing all hierarchies to the wind, with the exception of one. There is “I” and there is the world. I am a part of the world in life and in death. The universe could have me either way. There is all that has come and gone before me, composing the ground on which I stand. There is all that will be, which only the universe can determine. I am hanging precariously in the balance. The sublime is the realization that my life is small and fragile, yet in death I become part of something large, something infinite.

Schopenhauer further clarified the stages of depth into the sublime, and at each level the observer steps a bit closer to death until she is teetering on the brink, barely balancing on the edge. All stages of the sublime exceed the intensity of beauty – from the light reflected off stones (mildly threatening lifeless objects), to an endless desert (which cannot sustain the observer’s life), to turbulent nature (uncontrollable violent and destructive forces), culminating in the “fullest feeling of sublime” when experiencing the immensity of the Universe’s extent or duration such that the observer becomes aware of their mortality, their fragility, and their oneness with Nature.5

To experience the sublime is a hidden pleasure, one we find hard to admit even to ourselves. It is why natural disasters are so thrilling to us, in spite of our assertions otherwise. It is why thunderstorms elicit an electric current within us, a tingling cocktail of fear and excitement coursing through our veins.

However, once contact is made, the sublime can exist for us no more. Once destruction or death is actualized, the sublime instead becomes devastation or loss. As such the sublime is about potentiality. It occupies a space very rare, along with Schrodinger’s cat, where the wave function or quantum state collapses once an actual measurement is taken. The sublime is in-between, hanging in a precarious balance neither here nor there but both here and there.

The sublime is not purely philosophical; it is physiological. Its effects can be measured by heart rate, perspiration, dilated pupils. When one experiences the sublime she enters a state of heightened arousal in which she becomes hyperaware. The observer becomes aware of more than the immediate stimuli around him. One becomes aware of one’s own mortality. Simultaneously, one gets nearer to death and closer to life.

More than occasionally the sublime flirts with the ephemeral and the auratic. Indeed the sublime can be induced by the untouched natural world, while standing at the base of the snow covered Alps on a particularly hazy day, or while floating along at sea in the midst of a never-ending plane of murky depths. However, the sublime can also be induced by designed spaces. It can be brought on by massive yet delicately detailed buildings such as Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, where the combination of materials, high ceilings, and natural light dancing through polychromatic stained glass, evoke an overwhelming, indescribable, ineffable sensation. The sublime can be induced in spaces of anxiety – upon long bridges spanning over deep bodies of water, or standing upon the glass balconies 1,353 feet above ground at the Willis (Sears) Tower in Chicago. Though the occupant is assured the 1.5 inch thick glass is supported to hold five tons and there is no real threat of plummeting to the ground, the imagined potential of death provokes the sublime. As another example, the sublime can be induced at spaces where one may maintain anonymity while observing the constant rush of humanity, echoing back in time, such as deep within the structure of Grand Central Terminal.

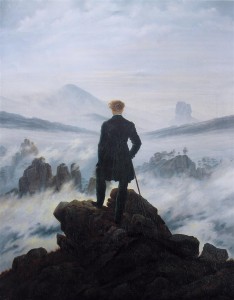

The sublime is inherently experiential, but perhaps the reason the original meaning has been lost today is because it is so difficult to represent. Two-dimensional representations have been made in three ways with varying degrees of success. The first method is the creation of an image of the experience with the sublimated individual in the frame. Examples of this technique can be found in the paintings by the Romantic artists of the 19th century, including Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1817 (Figure 1). Here the viewer of the painting is removed from the scene and takes an outsider’s perspective. The sense of the sublime may be understood in this method, yet due to the removal of the viewer it is less powerful.

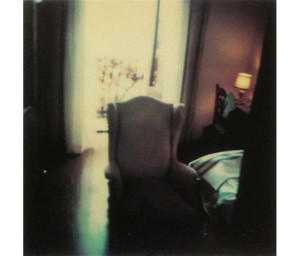

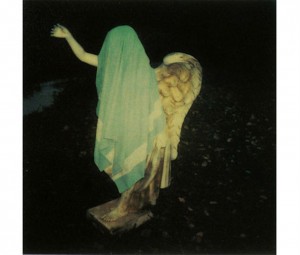

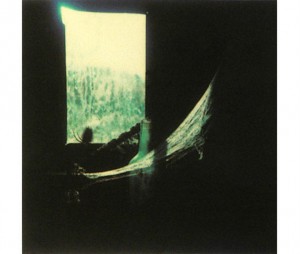

Another method of representation is first-person perspective of the sublime object or sublimation. This can be done in painting, and in modern and contemporary photography. Filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s recently digitized Polaroid photographs from the 1970s enter the territory of the sublime through a visceral spectral quality. Tarkovsky seems to have found the sublime in the every-day, from scenes of an armchair with washed-out light-soaked background to a small barn obfuscated by a heavy haze (Figures 2, 3). Many of the images taken in Russia and Italy are slightly jarring, haunting, foreboding. These pictures capture the sublime experience (sublimation) of Tarkovsky, yet offer back to the viewer a powerful visual aura. This representation is cyclical, as the viewer is put out of place, as was presumably the man behind the camera. Still, the sublime is impossible to describe, which corresponds with Tarkovsky’s warning: “Never try to convey your idea to the audience – it is a thankless and senseless task. Show them life, and they’ll find within themselves the means to assess and appreciate it.”6

The third means of representation is through the abstraction of the sublime itself. As Mallarmé said, “Paint, not the thing, but the effect it produces.” The difficulty with identifying representations of this type is that the sublime is essentially indescribable. It is hard to determine what differentiates a work abstracting the sublime from a work abstracting any common emotion. Though it may not have an effect on the quality of the piece and may actually add to artistic value, there will always be ambiguity in appropriating a work that attempts to describe a sensation through visual means.

Be it a representation or actual experience, the sublime is hardly predictable. It may sweep a person into its grasp at any time, when least expected, like the often mercurial nature of death itself. While the word “sublime” may have lost its potency, the capacity for sublimation exists today as powerful as ever. As long as the natural world exists along with man, the sublime will persist to the end of our dying day.

Figures 4-6

Notes:

1. Joseph Addison, Remarks on Several Parts of Italy etc. in the years 1701, 1702, 1703. (1773), 261

2. Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757)

3. Ibid., Part I, Section VII

4. Ibid., Part I, Section XV

5. Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1, trans. E. Payne, (New York: Dover Publishing Inc., 1969)

6. Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, (University of Texas Press, 1989)

Figures:

1. Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1817

2-6. Andrei Tarkovsky