Collective Identity and the Dutch Eye – exhibit

Robert S. Brown Traveling Fellowship 2012

[The Netherlands]

Description: The Netherlands is a country composed of a constantly changing collage landscape. It is a mixture of nature and artifice, urban and rural, water and land mediated by advanced technologies and grounded by the stability of a terrestrial horizon. From the Amsterdam School to De Stijl and Nieuwe Zakelijkheid, from the post-war reconstruction to the contemporary Vinex conditions, Dutch architecture is ironically unified in its diversity. Differing approaches have emerged out of various attempts to address the myriad constraints imposed on building and planning, particularly those concerning multi-unit housing. Collective identity is not based on a unified approach, but is instead established by embracing the differences and attending to the core values of the Dutch eye. Rigorous experimentation and inquiry can be traced back to the seventeenth century with Leeuwenhoek and Huygens, and regained strength in architecture with Rem Koolhaas in the 1980s. Dutch architecture has evolved over time through this inherited empirical curiosity. The visual culture of this country is determined not by sight alone, but by a multi-sensory depth of vision. This depth includes the synesthetic values of layering, density, superimposition, thickening, revealing, scalar juxtapositions, texture, and tonal detail consumed and inspired by the enigmatic Dutch eye.

Available in a print copy or digital download.

—–

INITIAL PROPOSAL

This proposal aims to explore the depth and multiplicity of sight as a holistic sense predicated on a responsibility toward the social collective, as it is continually refined/defined in Dutch architecture. The area of focus will primarily be urban housing from the 20th century onward, but will also include integral works from the Golden Age to present day.

The inspiration for this proposal stems from a desire to better understand multi-unit housing as a typology, as well as a desire to gain insight into the challenge of designing simultaneously for the individual and the collective whole. A longstanding interest in Dutch art, architecture, and the communication of culture through aesthetics has also had a prominent influence. Additionally, this proposal is informed by the urge to expose the constraining myth of the five senses, by focusing on a broader sensory modality including sensory overlap: specifically the haptics of sight which drive the Dutch eye. The very nature of this proposal is predicated on physical presence through experience and observation of the work as it is located in its social and global context.

While there is an abundance of discourse about the merits and qualities of Dutch architecture and its contribution to the field, there is still a vast range that has yet to be explored. The most understated, yet perhaps most important contribution by the Netherlands to modern architecture and beyond was the creation of a collective architecture. This first occurred when the individual house gave way to rows of houses in a collective assemblage in a series of streets, contributing to comprehensive unity. The implications of this collective social space are far-reaching to the profession and society as a whole.

THE DUTCH EYE: AN EMPIRICAL DEPARTURE

In the Netherlands during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the invention and refinement of both the microscope (Janssen, Leeuwenhoeck) and telescope (Lippershey, Huygens) displays the Dutch desire to see beyond what is there, to explore and elucidate what is not originally apparent in the visual field. This new way of seeing was a radical departure from classical rationalism, and was key to the development of art and architecture in the Netherlands. In this respect, the Dutch model of architecture draws more from science than pure mathematics. While 17thC Southern art (Italy, Spain, France) is based on explanation through rationality, hierarchy, proportion, and geometry (Cartesian perspectivalism), Dutch art and architecture aligns with an empirical experience based on observation and description. This is what Martin Jay calls the “Dutch art of describing” which he details as a scopic regime based on the writing of Svetlana Alpers. According to Alpers, Dutch art and architecture “casts its attentive eye on the fragmentary, detailed, and richly articulated surface of a world it is content to describe rather than explain.” There is no one situated viewer, no clear frame, no forced perspective. As a result the individual is granted the freedom of appropriation, which to this day is unequivocal in Dutch society.

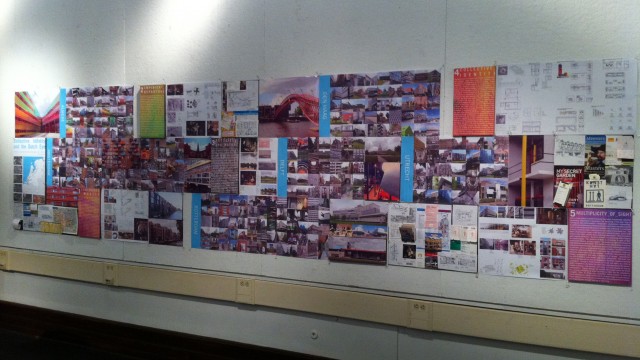

The art of describing lends itself to the depth of sight as a tool for understanding, and projected itself into the 19th century with the development of photography: fragmented scenes of a larger whole. This fragmentary nature and depth of sight will inform the criteria of the proposal, through photographic documentation and collage of detail, surface, and materials and methods of construction. The travel and documentation will attempt to engage these tenants in order to begin to see with a Dutch eye.

DEPTH OF SIGHT AND SOCIAL SPACE

There is a direct correlation between science, vision, and society in the Netherlands linked by this empirical departure in the 17th century. There is a curiosity prevalent across Dutch culture that extends to the public realm. With the individual now given the freedom of appropriation, architecture engages the public at a deeper level. This is integral to what Henri Lefebvre claims in The Production of Space, that “[social spaces] are made with the visible in mind: the visibility of people and things, of spaces and of whatever is contained by them. […] People look, and take sight, take seeing, for life itself.” While this is apparent in almost all Dutch architecture, the typology where these qualities of social space are most distinct and prevalent is urban housing. Many challenges arise in the design of multi-unit housing, but in the Netherlands they are ultimately addressed by the main tenants of the Dutch eye. Part of this exploration seeks to discover if a subjective objectivity can be reached in this type of empirical social space by designing for the individual within the collective whole.

OPPORTUNITY THROUGH CONSTRAINT

The Industrial Revolution began relatively late in the Netherlands, when Dutch capitalism took off in the 1870s with the boom in shipbuilding, production, and commercial business. With this came the concomitant emergence of industrial concentration, urbanization, and densification due to migration. In the early 20th century, the urban population spiked drastically, resulting in a housing shortage and poor living conditions. Instead of turning a blind eye to the blight, the Dutch government approached it as an opportunity for the architectural community to aid in the restructuring of the social conception of living space. Many rules and regulations were set in place through the Woningwet (Housing Act) along with the Public Health act. These codes and constraints did not inhibit the Dutch architectural imagination; on the contrary they were used as vast opportunities for design. Social-sector housing districts were not handed off to developers, but were instead considered as large blocks for the Gesamtkunstwerk as seen in Berlage’s Plan Zuid of 1917. Not only were these blocks the ‘total work of art’ but also a work of ‘community art’ or Gemeinschaftkunst, with the idea that a certain visual vernacular can have a positive effect on society. Whether this occurred or not, it is clear that the medium with which architects were designing was the same: social space through the empiricism of the Dutch eye. This mentality still prevails in Dutch architecture today.

THE GOLDEN AGE

In order to get a sense of the fundamental roots of Dutch aesthetic and social imperatives, it is important to experience urban constructs from the 17th-18th centuries. This will occur in an immersive way while walking through the city, by observing not only the buildings but also the entire urban fabric.

THE AMSTERDAM SCHOOL

The Amsterdam School (or the Wendigen Group – de Klerk, Gratama, Kramer) had no prescribed set of unifying architectural principles, aside from the tendency toward individual expression in the design of architectonic space down to the details. This included the use of symbols in sculpture, ironwork, and decorated glass in an almost allegorical way. This new visual vernacular and freedom of expression is seen in Michel de Klerk’s work, primarily in his three housing blocks in Amsterdam (1911-21). In these buildings, one can feel depth and texture through sight in the expression of material, and because of this a particular focus will be placed on the means, methods, and details of de Klerk’s work. Though de Klerk worked for Cuypers and influenced Berlage, his work is less about a rational, monumental whole and more about specific moments, scenes, and individual details which come together in a unified expressive picture.

A NEW VISION OF MODERNISM

The Traditionalism of the Amsterdam School was countered in the Netherlands by the De Stijl movement (Rietveld, van Doesburg) and CIAM Rationalism. However, in looking specifically at J.J.P Oud’s ‘white villages’ in Rotterdam, one can see how even the most pragmatic and reductive Dutch architecture acts as a social interface. Ironically, rationalism did not prevail for long, due to the reaction from the Forum Generation (van Eyck). There was a desperate call for a return to the roots, not necessarily recalling a certain style, but recalling the principles upon which the Amsterdam School was founded: expression of material, detail, and the responsibility to the social collective.

CONTEMPORARY IDENTITY, FUTURE TRAJECTORIES

Though over the years a distinct and unified visual style of Dutch architecture has all but been eradicated, the fundamental goals and desires remain stronger than ever. Urban social housing remains one of the most important building typologies in the Netherlands, and has only gained momentum. Contemporary constructions by MVRDV, OMA, die Architekten Cie, West 8, and other Dutch firms are refining the meaning of social space in an experimental way, especially along Borneo-Sporenburg, and the one-mile strip of housing in The Hague. The question of how we are to dwell in the future is one that pervades the architectural imagination, for example Adrian Geuze’s conceptual ‘Wilderness’ experiment for the empty space in the Sandstaad. These conceptions are near utopian visions of architectonic design always determined by societal reality.